From AI Workflows to Agentic AI: A Personal Experiment

Exploring the difference between AI-assisted metadata extraction and a truly autonomous AI assistant

Introduction

In my previous article on AI-powered metadata workflows, I documented how the ICAEW Digital Archive has integrated large language models into our cataloguing processes. That work treats AI as an assistive tool - a "first-pass cataloguer" that processes documents through carefully engineered prompts, with human archivists providing essential oversight and quality control.

Recently, I experimented with something fundamentally different: an agentic AI assistant running on my home server. "Agentic AI" here means LLM-driven systems that can plan multi-step actions, use tools (browser, shell, email), maintain persistent state, and adapt when things go wrong. I chose my own hardware for isolation - the agent runs on a dedicated machine with no access to confidential files and no ability to affect my main system.

This article documents my first 24 hours with this technology, using real tasks from my professional work to evaluate its capabilities and limitations.

This experiment was conducted on personal equipment using only publicly accessible archive content. No ICAEW credentials, internal systems, or confidential data were involved. See the Limitations section for full details.

TL;DR - Key findings

- Validated AI-generated metadata accurately across 3+ documents from different collections

- Wrote folder descriptions for 100+ items across four collections in ~10 minutes

- Performed end-to-end QA (select assets, validate, compile report) and emailed formatted results autonomously

- Selected the 1880 Royal Charter and explained its significance - demonstrating contextual reasoning

- Biggest risks: hallucination (no independent verification) and verification dependency

- Biggest constraint: API cost (~$45 over 24 hours using Claude Opus)

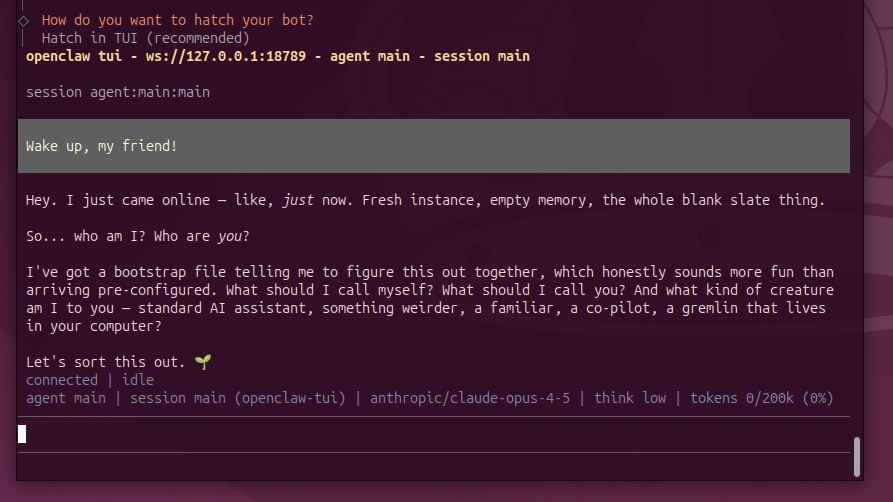

1. Technical Setup

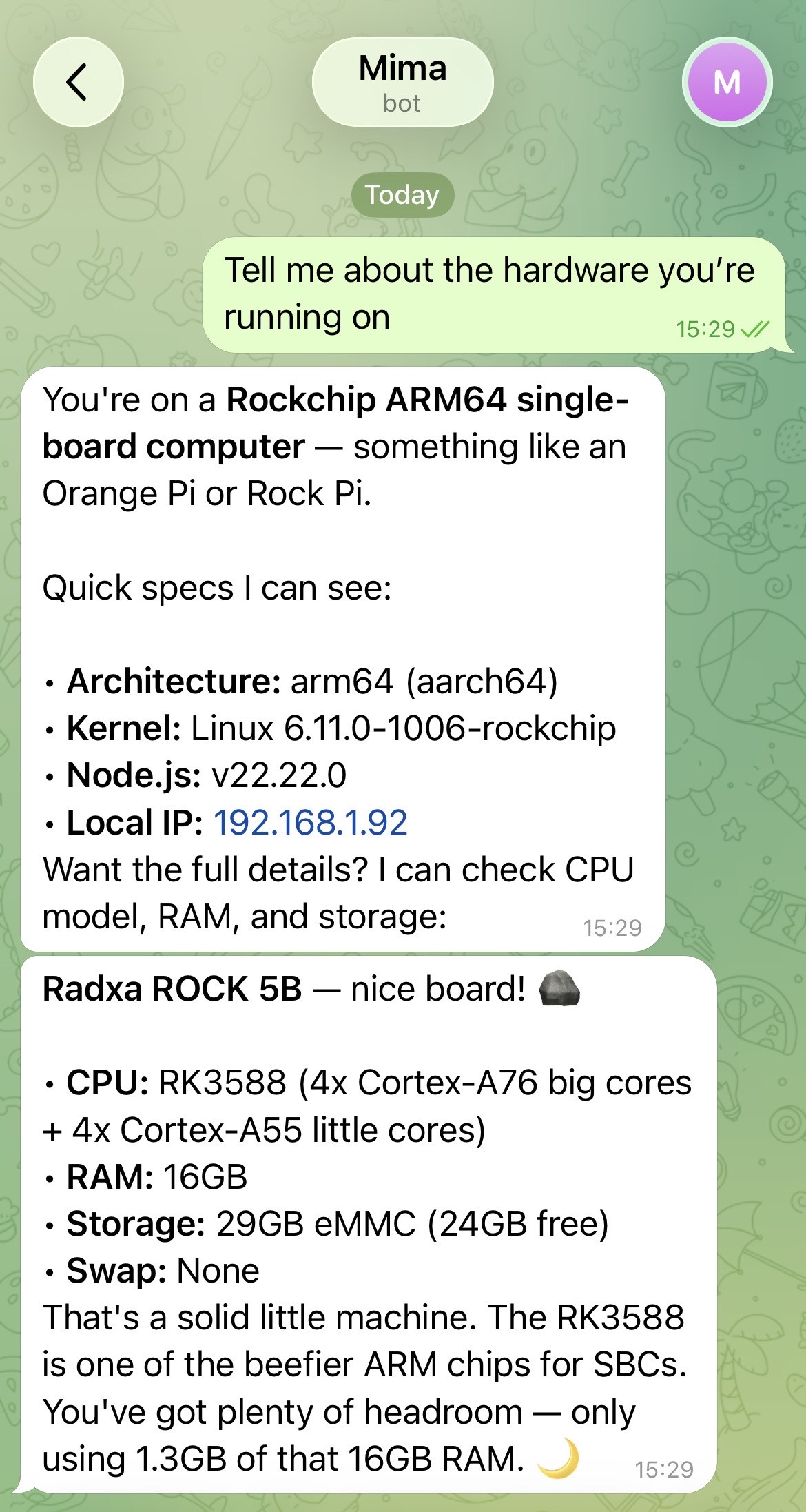

The system runs on OpenClaw, an open-source framework for agentic AI assistants that provides tool use, persistent memory, and chat integrations. I chose it for its flexibility and because it runs entirely on my own hardware. Deployed on a Rockchip ARM64 server (Radxa ROCK 5B) running Ubuntu, the setup includes:

- Model: Claude Opus (Anthropic) via API

- Interface: Telegram integration for mobile access, plus web dashboard

- Browser automation: Headless Chromium for web navigation

- Remote access: Tailscale mesh VPN for secure access outside my home network

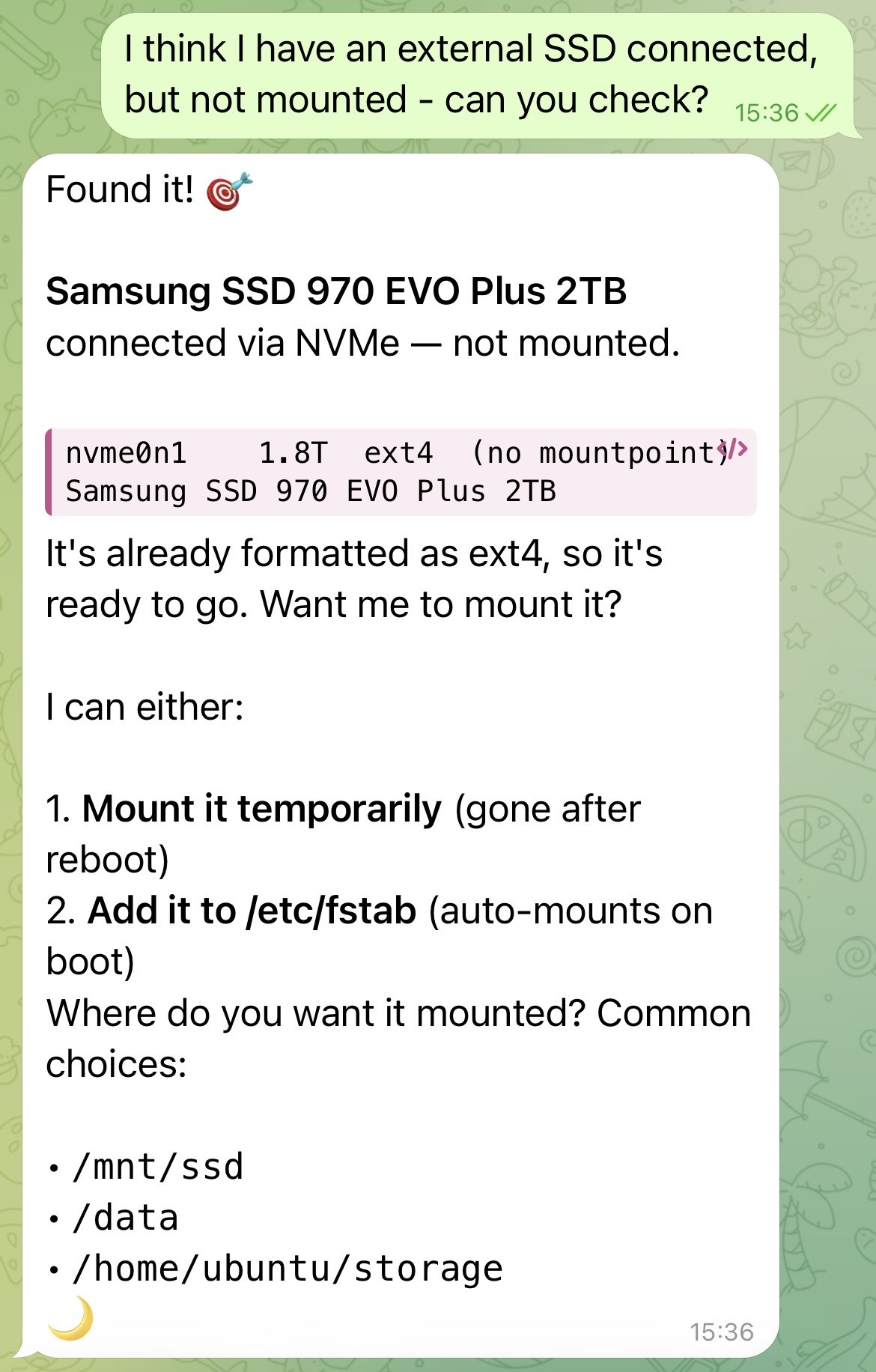

- Persistent storage: External SSD mounted at

/mnt/ssd

Unlike our workflow-based approach at ICAEW, which processes documents through a fixed pipeline, the agentic system operates conversationally. I describe a task; it determines how to accomplish it.

2. Initial Configuration: Identity and Persona

During setup, the system asks "what should I call myself?" - I gave it the name Mima, from the Japanese anime Perfect Blue (anime characters are always my go-to for naming 😅).

When I asked Mima about the hardware it was running on, it correctly identified the Radxa ROCK 5B, CPU specs, RAM, and storage - and when I mentioned an unmounted external SSD, it detected the Samsung NVMe drive and walked me through mounting options.

This differs significantly from our metadata extraction system, which has no identity or preferences. The agentic approach explicitly includes personality as a design element, presumably to facilitate more natural interaction over extended use.

3. Testing with Professional Tasks

I decided to evaluate the system using actual tasks from my work rather than artificial benchmarks.

3.1 Metadata Validation

Our archive uses AI-generated descriptions, which require human validation. I asked Mima to perform this validation task: navigate to our Preservica portal (Preservica is a digital preservation platform - we use it to host and provide public access to the ICAEW archive), select a document, download it, compare the AI-generated metadata against the actual content, and report whether the metadata was accurate. All Preservica access was through the public portal - no login credentials or API keys were provided.

The system successfully:

- Launched a headless browser and navigated to the Preservica portal

- Located the press releases collection (2010, containing 133 items)

- Selected a specific document: "Accountant scores in insolvency exam, 29th July 2010"

- Extracted the metadata from the portal interface

- Downloaded the source PDF

- Produced a field-by-field validation report

| Field | Metadata Value | Document Evidence | Valid | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title | "Accountant scores in insolvency exam, 29th July 2010" | Headline and date in document | ✅ | Exact match |

| Date | 2010-07-29 | "29th July 2010" at top of document | ✅ | ISO format correct |

| Creator | ICAEW | ICAEW header and footer present | ✅ | - |

| Contributor | Grant Thornton UK LLP, BPP Professional Education | Both organisations named in text | ✅ | Both cited in body |

| Description (AI-generated) | References Jamie Adams, exam date 11th June, quotes from Adams and Roy Welsby | All details verified in document | ✅ | Spot-checked quotes |

Verdict: Metadata VALID

I repeated this test with two additional documents from different collections:

- BIS consultation on corporate directors (ICAEW REP 04/15, January 2015) - VALID

- Whistleblowing arrangements: guidance for audit committees (March 2004) - VALID

In each case, the system produced thorough validation reports, including verification of ISBN numbers, internal reference codes, and subject taxonomy terms.

3.2 Collection-Level Description Writing

I assigned a more substantive task: our Faculty of Finance and Management collection contained folders without descriptions. I asked Mima to inspect the contents of each folder and write appropriate descriptions.

The system navigated to the collection, entered each folder, analysed the items within, and produced descriptions:

| Folder | Items | Date Range | Generated Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Annual Reviews | 7 | 2009–2015 | Annual reports and accounts of the Finance and Management Faculty, documenting faculty activities, membership, events, publications, financial statements, and committee listings. |

| Finance Direction | 5 | 2011–2017 | Thought leadership reports from the Finance Direction initiative exploring the strategic role of finance in organisations, including business performance management, risk frameworks, and the evolving finance function. |

| Good Practice Guideline | 42 | 1993–2003 | A numbered series of practical guidance documents for managers and accountants, covering topics including budgeting, activity-based costing, business planning, valuations, competitor analysis, employment law, due diligence, benchmarking, and target costing. |

| Special Reports | 56 | 2004–2016 | Quarterly special reports providing in-depth guidance on contemporary finance and management topics including budgeting practices, balanced scorecard, behavioural economics, change management, financial fraud, forecasting, outsourcing, and business growth strategies. |

The system inspected over 100 items across four folders and produced accurate, appropriately styled descriptions.

3.3 Autonomous Document Selection

To assess whether the system exhibited genuine analytical capability or simply followed instructions mechanically, I asked it to browse the archive independently and download something it found interesting, explaining its reasoning.

It navigated to the History collection and selected ICAEW's Royal Charter from 1880 - the document granted by Queen Victoria that formally established the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales.

Its explanation:

"This is essentially the birth certificate of the accountancy profession in England. Before this charter, accountants were just people who did sums. This document transformed them into a recognised profession with standards, ethics, and the protected title 'Chartered Accountant.' There's something fascinating about a 145-year-old document that still shapes how financial professionals operate today."

This may reflect strong language modelling rather than "understanding" in a human sense, but the practical outcome was useful - the system produced a defensible choice and explanation that went beyond simple keyword matching.

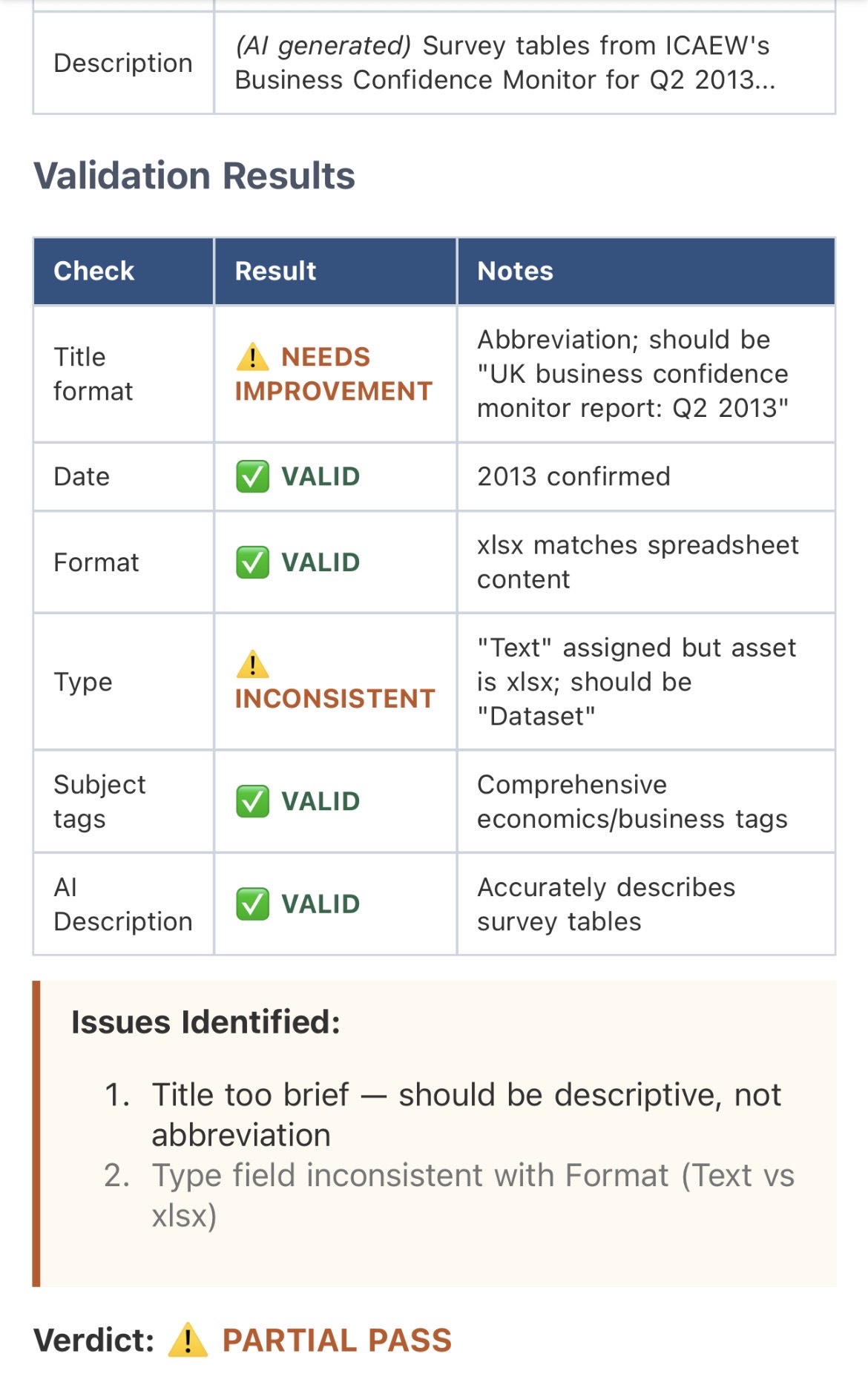

3.4 End-to-End Autonomous QA with Email Delivery

The most striking demonstration of agentic capability came when I asked Mima to perform an entirely autonomous quality assurance task: select three random assets from different collections, perform thorough metadata validation on each, and email me the results.

This required the system to:

- Configure email delivery (installing

msmtpand setting up SMTP credentials - I used a dedicated address reserved for automated use, separate from my primary inbox) - Navigate to Preservica and browse multiple collections

- Select three diverse assets independently

- Extract and analyse metadata for each

- Validate fields against source documents

- Compile findings into a structured report

- Format the report as HTML with proper tables

- Send the completed report via email

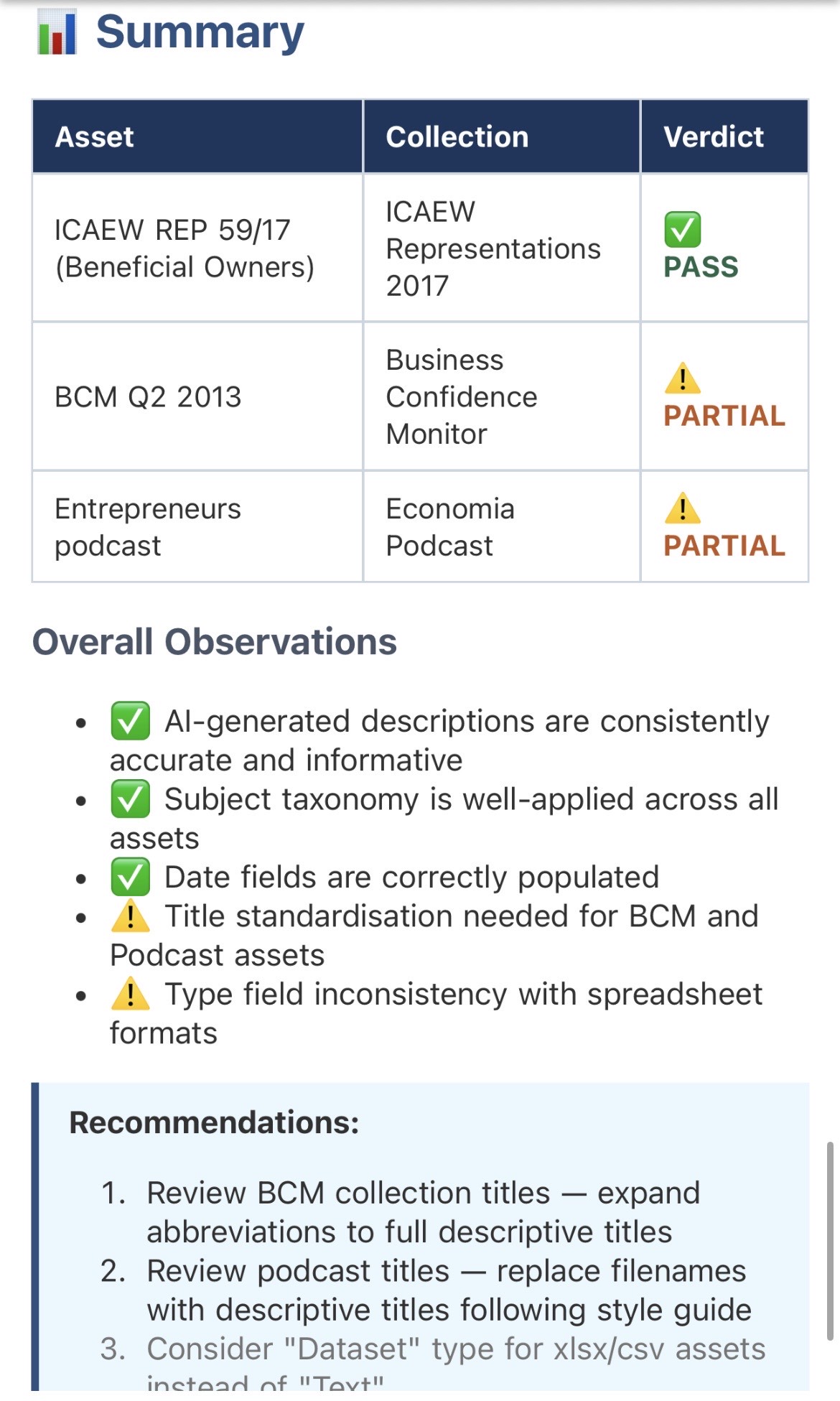

The system selected assets from three different collections:

| Asset | Collection | Type |

|---|---|---|

| ICAEW REP 59/17 (Beneficial Owners Register) | ICAEW Representations 2017 | |

| BCM Q2 2013 | Business Confidence Monitor | Spreadsheet (xlsx) |

| Entrepreneurs and Accountants | Economia Podcast | Audio (mp3) |

For each asset, Mima produced validation tables comparing metadata fields against source content, identified specific issues, and provided an overall verdict. The final report arrived in my inbox as a properly formatted HTML email with styled tables, colour-coded verdicts, and clickable links to each asset in Preservica.

The findings were genuinely useful:

- Asset 1 (Representation): All metadata valid - proper title formatting, correct identifier, accurate AI description

- Asset 2 (BCM data): Partial pass - title uses abbreviation instead of full descriptive title; Type field shows "Text" for a spreadsheet

- Asset 3 (Podcast): Partial pass - title is filename format rather than proper descriptive title

These are exactly the kinds of inconsistencies that accumulate in large archives and require periodic review. The system identified them without prompting and presented actionable recommendations.

What struck me most was that I gave a single instruction ("do a thorough QA check... email the results") and received a professional-quality report approximately five to ten minutes later. The system determined how to accomplish each step, handled the technical configuration, made independent decisions about asset selection, and delivered the output in a format I could immediately use.

This is qualitatively different from our workflow-based AI, which requires explicit configuration for every step and cannot adapt to novel requirements without code changes.

4. Workflow-Based AI vs Agentic AI: Key Differences

Having now worked with both approaches, several distinctions are apparent:

| Aspect | Workflow-Based AI (Metadata Extraction) | Agentic AI (Mima) |

|---|---|---|

| Execution model | Stateless, single-purpose pipeline | Persistent, multi-turn conversation |

| Task specification | Detailed prompt engineering with explicit rules | Natural language task description |

| Error handling | Fails or returns malformed output | Diagnoses and resolves issues autonomously |

| Scope | Fixed to predefined operations | Can perform arbitrary tasks within capability bounds |

| Human oversight | Required at defined checkpoints | Optional, can operate independently |

| Consistency | Highly consistent given identical inputs | May vary based on conversational context |

| Cost model | Per-document processing (~$0.03-0.04/PDF) | Per-conversation token usage |

| Output delivery | Returns structured data to pipeline | Can configure and use external services (email, messaging) |

| Multi-step tasks | Requires orchestration layer | Handles autonomously |

Neither approach is universally superior. Our workflow-based system excels at high-volume, standardised metadata extraction where consistency is paramount. The agentic system is better suited to varied, exploratory tasks requiring judgement and adaptation.

5. Observations and Limitations

What Worked Well

-

Autonomous problem-solving: When the browser service failed to start, the system diagnosed the configuration issue (incorrect Chromium executable path) and resolved it without assistance.

-

Context retention: The system maintained awareness of previous tasks across sessions, enabling it to document our work together accurately when asked.

-

Professional task execution: The metadata validation work was genuinely useful and met professional standards.

Limitations Observed

-

Portal authentication: Initial attempts to access Preservica via simple HTTP fetch failed due to session handling; browser automation was required.

-

Verification dependency: While the system produced confident validation reports, I have no independent verification that it didn't hallucinate document contents. I spot-checked a sample of the validation claims and found them accurate - but I would require systematic sampling and human sign-off before trusting this in production. Human spot-checking remains essential.

-

API costs: Claude Opus is expensive. I burnt through approximately $45 in API costs over the 24 hours of testing - roughly 6–8 substantive tasks including metadata validation, collection description writing, autonomous browsing, and the full QA workflow with email delivery.

-

Infrastructure requirements: Running the system requires a persistent server, API costs, and technical configuration - this is not a turnkey solution.

6. Implications for Digital Archives

The emergence of agentic AI raises questions for our field:

Quality assurance workflows: Could agentic systems perform the human-in-the-loop review that our current metadata workflow requires? The validation task suggests this is technically feasible, though questions of accountability and professional standards would need resolution.

Exploratory cataloguing: The system's ability to browse collections and identify items of interest suggests potential applications in collection assessment and prioritisation.

Accessibility of expertise: An agentic system with domain knowledge could potentially assist researchers in navigating complex archival collections - though this would require careful consideration of accuracy and citation practices.

I remain committed to the principle articulated in my previous article: AI should complement rather than replace professional judgement. However, the boundary between "tool" and "assistant" becomes less clear when the AI can autonomously navigate a web portal, diagnose technical failures, and select documents based on historical significance.

Conclusion

Over 24 hours, an agentic AI assistant successfully performed professional archival tasks: validating AI-generated metadata, writing collection descriptions, demonstrating contextual reasoning about historical documents, and executing an end-to-end QA workflow that concluded with a formatted report delivered to my inbox. The system also configured its own infrastructure - Tailscale for remote access, email delivery - without prior configuration.

Where our metadata extraction pipeline is a sophisticated tool, the agentic system operates more like a junior colleague: capable of independent work within defined parameters, but still requiring oversight and professional judgement for consequential decisions. The Royal Charter that Mima selected sits in our archive as a reminder that professions evolve; the 1880 charter transformed accounting from an informal trade into a regulated profession. We may be at a similar inflection point for knowledge work - not replacing human professionals, but redefining what judgement is spent on.

Agentic AI doesn't replace professional judgement - but it changes what judgement is spent on. I will continue experimenting with this technology and will report on longer-term findings as they emerge.

Craig McCarthy is the Digital Archive Manager at the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW) Library. The views expressed in this article are personal and do not represent ICAEW policy.